designed for the way women work.

Rebecca Webster, Citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin

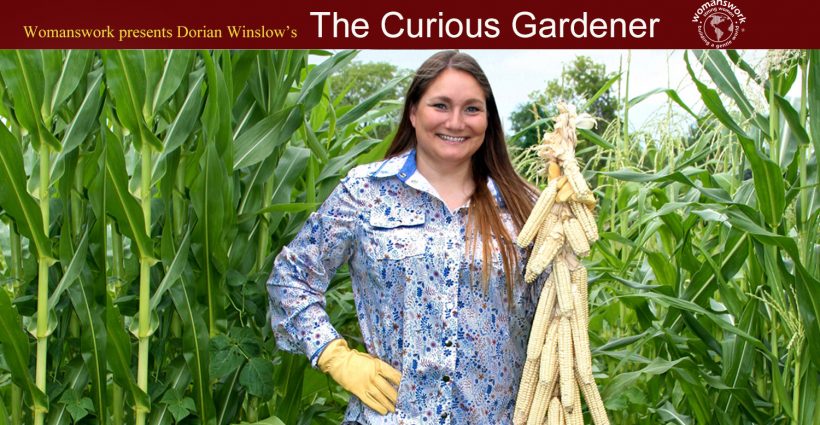

Category: Presenting "The Curious Gardener"

Rebecca Webster is not your average attorney, teacher, activist, farmer and mom. She’s a proud citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin whose passion to reignite the traditions of her forebears is evident in everything she sets her mind to.

Soft spoken and upbeat, Rebecca tells me in a phone interview that she grew up on the reservation but was bussed to public schools off the reservation. At that time there was not a lot of interest in understanding the culture of her tribe, on or off the reservation.

Thankfully, it’s different now, she says. “Our people are reconnecting and reclaiming our identity,” says Rebecca. Even the public schools have resources available to share knowledge about Native American history and traditions. Nevertheless, her two teenage daughters, ages 14 and 16, are home schooled by her husband on the reservation where they live. Their education is steeped in tribal culture.

With several academic degrees under her belt, including a doctorate in Public Administration and Policy, Rebecca decided to make some important career changes in 2016. She calls it ‘the perfect storm’ when she decided to stop practicing law (having served the Oneida Nation for 13 years) and begin teaching (tribal administration and governance at the U. of Minnesota), freeing up her summers. Her husband left his career and they bought a 10 acre farm on the reservation. An Oneida faithkeeper named their farm Ukwakhwa: Tsinu Niyukwayay^thoslu, which translates to Our food: Where we plant things, in English.

With all the building blocks in place, they took action on their dream of creating a community hub at their farm for sharing knowledge about traditional Native American practices, including planting, growing, harvesting, seed keeping, food preparation and food storage.

Rebecca’s own childhood is a perfect example of how the traditions had been lost for a long period of time. Her great grandmother was the last in her family to grow white corn, which is considered sacred to the Oneida Nation. Rebecca loved corn soup growing up, but corn is labor intensive to grow. Her parents grew the occasional tomato plant or snap peas, says Becky, but gardening was just not something they talked about or endeavoured to improve on.

In the 1970’s the Tribe, or local Native American government, began growing corn on a small scale to distribute to families on the reservation, but for years the demand was low because it was seen as something reserved only for special occasions. Over time, however, demand grew and they couldn’t keep up with it.

That’s when Rebecca joined with other families to form a co-op and grow corn together. They are gradually adding other crops such as squash and beans, as Rebecca collects and shares her seeds with them. Seed collecting and sharing is considered a sacred act in her culture.

The Three Sisters

Corn, beans and squash are called ‘The Three Sisters,’ staples of the Oneida Nation diet. “The corn grows tall and strong, providing sustenance to the people. It serves as a pole for beans which add nitrogen to the soil as they grow. Squash is planted at the base of the corn. Its broad leaves and prickly stems keep weeds at bay and prevent foraging animals from taking more than their fair share,” says Rebecca.

“The Three Sisters” are the primary crops grown on Becky’s farm, along with sunflowers, strawberries, tomatoes, cucumbers and melons. “We plant enough for ourselves and the animals too”, says Becky. “The racoons, rabbits, deer, and even the bugs.”

The concept of plant communities, where certain plants are advantaged by growing alongside certain other plants, may be touted as a breakthrough concept in mainstream horticultural circles these days, but it’s as old as the Creation Story, or original instruction, among Native American peoples.

All kinds of corn are indigenous to her people, but white corn is the most commonly grown. It appeared in the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Creation Story, an oral tradition that predates the arrival of the white settlers. The Oneida Nation is one of 6 tribes or nations in the Iroquois Confederation. In the early 1800’s the Oneida Nation removed to Wisconsin from New York State.

Rebecca grows it for multiple purposes. Some of it, called “green corn,” (the stalks and leaves are green, though the corn is yellow) is harvested to eat and mush into paste for cakes and breads. It’s sweet. Most of the corn is left in the fields until the stalks are brown and crispy though. That corn is braided in long braids to dry further. In March or April the following year the seeds are taken off and stored for planting and for sharing. The husks are made into cornhusk dolls!

She grows about 20 varieties of pole beans or half runners, but avoids any that are so vigorous they could threaten to pull down the corn. Squash is not safe with cross pollination she says, so she stays with the Oneida hubbard squash.

An Assertion of Sovereignty

Rebecca’s farm takes up a large expanse along a main road through the reservation. Cars drive by slowly so people can see and ask questions. “It gives us a chance to assert ourselves and say ‘We’re still here. We’re proud of who we are.’ We want others to be excited about what we’re doing too,” says Rebecca.

Every seed they plant on their farm is an assertion of sovereignty.

Rebecca is wearing Womanswork Deerskin gloves on her farm in Wisconsin.

For more information about Rebecca’s activities visit these websites:

youtube.com/channel/UCedwwKoqSpSD1pCYvfpUXbw?view_as=subscriber

This is a story that is amazing in many aspects. The biography of Rebecca, the history of her tribe, the tips on horticulture. Is there an archive or library that collects stories like this? So many of the Native Americans have had to use ‘casino’ type activities to support themselves, or solicit donations to support the tribal children. When buying books for children, this is one I would choose.

Best wishes to all.